Myst and its production makes a text worth reading, in part because of the way it reminds us of what we know but are continually tempted to forget: that no text–much less hypertext–is an island.ĭespite its graphical interface and its being marketed as a virtual reality game, Myst is fundamentally a hypertext product. When the stand-alone CD-ROM game is situated in the context of cultural production (in this case, materially, the publishing enterprise), the world-making impulse figured in the very structure of the game, as successive or parallel “ages” or technological regimes, tellingly gives way to messier arrangements in the social nexus–extraneous networks, intertexts, contradictory modes of production, overlapping markets of users, hybrid notions of genre, sparse or tangled, end-less webs of provisional links.

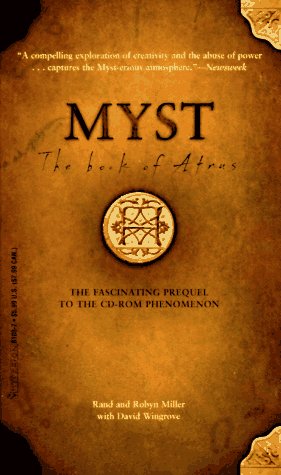

Even if we grant the phenomenological differences between a literally textual and a graphical environment, theorists of hypertext would do well to pay attention to Myst and what it reveals about the place of the Book at this late moment in the history of print culture. 1 Only the Web as a whole has allowed more users to follow more forking paths to unexpected if not indeterminate ends. My point of departure is the fact that the 1993 Broderbund-Cyan CD-ROM game Myst has sold an estimated two million copies to date, making it among the most widely experienced hypernarratives (if not, strictly speaking, hypertexts) in our time.

Loyola University is a registered trademark of Cyan, Inc.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)